Extreme Championship Wrestling’s Heatwave ’98 pay-per-view was exceptional in many ways.

Pro wrestling was in the middle of its late 1990s boom and ECW was at its peak. Heatwave ’98 was the company’s most successful PPV and the second-largest crowd.

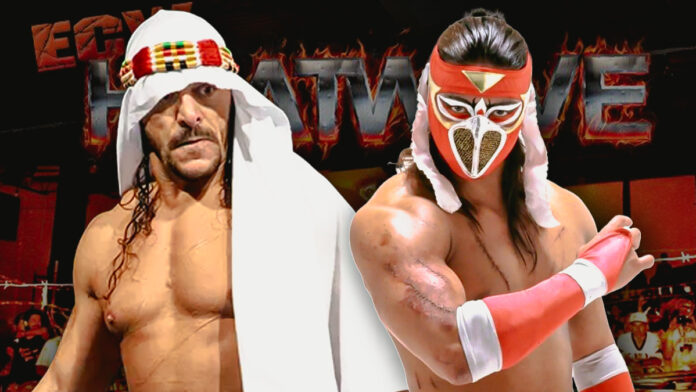

Sabu was the wrestler that innovated ECW into the minds of American pro wrestling fans. Trained by his uncle, The Sheik, Sabu followed in his footsteps as a silent, disturbing foreign villain. The Sheik was one of the industry’s greatest draws with a penchant for violent matches, blood and guts.

Add an uncanny natural athletic ability (think Ricochet), one part devoted adrenaline addict (Darby Allin), and a lack of fear of blood, heights, barb-wire, flame, glass or any other (Jon Moxley, Terry Funk, Mick Foley), Sabu was the perfect evolution of his uncle.

He paired perfectly with fellow Sheik trainee Rob Van Dam, the brash, stoner, the Whole F’N Show and Mr. Monday Night, and the loud, whistle-blowing former ref turned manager Bill Alfonso. Their promo packages were a mix of Van Dam’s showboating, Alfonso’s antics and Sabu’s facial expressions, ironically similar to a confused Tazmanian Devil when confronted with Bugs Bunny.

Hayabusa

If there was a Sabu of Japan, it was Hayabusa. The top star in FMW, his appeal was similar to Sabu – you never knew what would happen anytime he was in the ring. Years before he was paralyzed in 2001, Hayabusa landed nearly head first after a Shooting Star Press. The match was showcased on FMW video tapes sold in the U.S.

An innovator, he popularized the Falcon Arrow, a move used by dozens of wrestlers including Seth Rollins among others. Jinsei Shinzaki wrestled briefly for the World Wrestling Federation in the mid 1990s, a capable wrestler who was famous for his praying ring walk and body tattoos. His build and look screamed badass. As a special attraction, the match couldn’t have been better put together. As a tag team match, it was an event.

We were in the deck above the floor, nearly straight across where Bam Bam Bigelow and Taz would crash into the entrance ramp. Electricity is often used to describe crowds, but this one was different. Before the show, fans were chanting E-C-W for hours in the parking lot and over an hour before the show in the arena. Tammy Sytch and Al Snow, who was backstage but not part of the event, came to the ring before the pre-show. They were in awe of the sold out crowd of devoted ECW cultists, the hours of chants. The line of fans who circled the large Hara Arena complex.

ECW’s milestone show

This was ECW’s first show in the Midwest. The company almost exclusively operated in the Northeast. Prior to picking Hara Arena in Dayton, Ohio, the company was looking for a venue in or near Indianapolis. One wasn’t available. Hara was quickly brought up as an appropriate replacement.

Dayton had a reputation as a diehard wrestling town. The town was the territory of The Sheik’s Big Time Wrestling for years, until the company went out of business in the 1970s. After came a territory war that saw Southwest Ohio become one of the wrestling hotbeds in the world. Dayton and Cincinnati were big business towns, home of military bases, auto and jet manufacturing and a century of inventive history – this meant a lot of money was in the neighborhood.

Georgia Championship Wrestling, Mid-Atlantic/Crockett Promomtions, the WWF, the AWA and Bruno Sammartino’s promotion in Pittsburgh tried burrowing the way into the area. The first match between Ric Flair and Hulk Hogan happened at Hara in 1991, a deliberate test match in front of Dayton fans unannounced and taking place at a house show. WCW’s 1997 Sould Out PPV was at the arena the year before. WWF ran major house shows at Hara for years before moving to Wright State’s arena in 1990. This means fans were used to different styles and were smart.

The location was also a draw. ECW was suddenly much closer – and it was a PPV. Cars in the parking lot sported license plates from every state from the Rockies to the Midwest and a few further to the West. This made the show an even bigger event.

ECW wrestlers knew of the arena’s significance and the history of promotions who ran it – and they had sold it out, to a crowd chanting the name of their company for hours before the show. After years of building the company through tape trading, syndicated TV, shows at bars, clubs and wherever they could get booked, Heatwave ’98 had cemented the company as a major promotion.

Seeing something new and in front of 5,000 fellow human beings is a different experience. Things slow down. Every moment stays. Your mind doesn’t wander. That’s what being in the crowd was like.

Tough act to follow

The tag match started slow, as it should have following Mike Awesome and Masato Tanaka’s first PPV match. While the tag match is what people most remember, the brutal Awesome/Tanaka match was another gift of the FMW/ECW partnership. It’s hard to follow two crazies powerbombing each other out of the ring and through tables and blasting each other with chairshots. The match was brutal, entertaining and a spectacle. It was also everything wrong with pro wrestling in the 1990s. It was careless and dangerous at best.

Van Dam and Sabu were arguing over who would be in the match first, nearly coming to blows. I was near a group of fans who began cheering for Sabu while he stood on the apron. Sabu, living his character by the second, acknowledged the fans and took that as a cue to enter the ring. The referee ushered him back, but Sabu nearly punched him for his trouble.

The character building, the time to cool off following Awesome/Tanaka, the little bits of dissension, reviewers at the time thought the match was devoid of psychology, but it was full of it. The story of the match was the four guys in the ring and what they brought as innovators. They weaved this slowly through some matchups. Hayabusa establishd his team as the heels early by punching Sabu in the face while in he stood on the apron. Sabu and Van Dam worked limbs in between their bigger moves. Hayabusa and Shinzaki followed suit.

The match wasn’t perfect. Van Dam and Hayabusa had a couple miscommunications early, but they got into the flow. Shane Douglas, then ECW World Champion and on commentary, noted how Sabu and Van Dam had adjusted their style to fit a strategy – “from reckless abandon” to “organized strategists.”

The match heated up after Van Dam interfered without a tag. Sabu had Hayabusa in a half Camel Clutch. Van Dam jumped in with a springboard backflip into a dropkick on the locked up Hayabusa. Shinzaki wasn’t happy and knocked Van Dam out of the ring with a brutal springboard dropkick while RVD posed.

Hayabusa with an asai moonsault. Sabu with a chair-assisted splash into the crowd. Van Dam laid out Hayabusa on the guardrail before jumping off the apron with a corkscrew legdrop. Hayabusa with a springboard senton splash, Shinzaki with a springboard knee drop.

Fans had been standing for most of the show. This was the rare match where “what would happen next?” was the story. The teams traded off tag team moves. A bow and arrow with a top rope chair smash to the ribs. A double bulldog. A standing heel kick into a german suplex.

The 5-star Frogsplash and the finish

The most memorable moment of the match followed Sabu’s springboard top rope hurricanrana on Shinzaki. Van Dam had been outside the ring and had disappeared from view. Shinzaki landed near the ropes on the far left side of the ring from the hardcam.

In the arena it might as well have been half a football field. To PPV viewers, Van Dam came flying out of the top of the screen. The Five-Star Frogsplash would become Van Dam’s finisher but at this point in his career, it was becoming a staple move. Eddy Guerrero popularized the move when he was in ECW, using it in honor of his tag team partner Art Barr. Van Dam’s frongsplash had a literal twist. He would jump and mid-air shift 90 degrees landing sideways.

Van Dam was a special wrestler because he was a special athlete. He could do things no one else could. He could leap to a turnbuckle in perfect balance. His frogsplash wasn’t another finishing move, it was worth the price of admission. Watching him leap from the floor, to the apron, to the turnbuckle, and fly three-quarters across the ring was a feat of rare and singular athletic ability. I’d seen the move on ECW TV, I’ve never seen him land it like this.

He traveled across the ring and gained height as he twisted. It’s a singular move and a singular moment.

Van Dam was a reflection of Sabu. Every Sabu match was a singular moment. RVD was his mirror. The chairs, the splashes, the flash, the kicks, he leaps – the perfect tag partner for the most innovative wrestler of the last 30 years.

Shinzaki powerbombed RVD, setting him up for a 450 Splash from Hayabusa, one of the best to perform the move. Van Dam countered with a top rope Van Daminator that spanned one turnbuckle to the next.

The match ended with a table. With Hayabusa on one side and Shinzaki on the other, Van Dam Sabu leapt off opposite turnbuckles with dual leg drops. Sabu made the pin ending the match. The crowd roared.

Aftermath

The match was the highlight of the PPV of the year, an award it won in the Wrestler Observer Newsletter that year. The fans felt that way.

There was a party atmosphere during the entire show, but the tag team match pushed it to another level. It was euphoric. Cars blasted “Walk” by Pantera, RVD’s theme at the time. Fans cheered. They went in search of wrestlers and autographs. Getting out of the building was difficult, getting out of the parking lot was worse. The PPV felt like a major concert more than a wrestling show. it was a party.

Watching the match nearly 30 years later, the most notable was the pace of the match. This wasn’t a race and there wasn’t long pauses between big moves. Today, this match would have been more calculated, with today’s wrestling norms replacing the ones of the late 90s. The big spots were setup quick, there was no waiting for people to get in place. Wrestling filled the gaps. It’s a match that belongs in different eras.

The figure who made the match and the show and ECW’s success was Sabu. Without Sabu, Rob Van Dam doesn’t develop his style. ECW doesn’t become a national promotion. Hayabusa doesn’t exist. FMW would have become something else. Table spots wouldn’t have been a thing weekly on WCW and WWE TV, for better or worse.

Three short years after its biggest show, ECW was shut down, its copyrights purchased by the WWF. Outside of one great angle on an episode of Raw, and the original One Night Stand PPV, the company was gone. WWE’s joke of a revival was the equivalent of Pat Boone performing as The Ramones.

A month after ECW shut down, Hayabusa’s career ended when he was paralyzed. After regaining his ability to walk in the 2010s, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 2015.

Sabu wrestled for a time in the WWE revived ECW. He regularly wrestled in TNA and independent shows. He appeared for AEW in 2023 as an enforcer for Adam Cole against the Jericho Appreciation Society.

Three weeks ago, Sabu wrestled his retirement match against Joey Janela at GCW’s Spring Break 9. The match was in his hometown of Las Vegas. Dead at 60 years old, he outlived many of his ECW locker room contemporaries, but died young.